KWESI

Kwesi, a Ghanaian asylum-seeker fled Ghana escaping religious persecution. However, upon arriving to the US border he was held in indefinite detention for almost two-years.

Kwesi, a devoted Christian refused to become the next voodoo priest of his village in Ghana and he was persecuted for it. Fearing for his life he fled to South Africa, through Brazil and arrived at the US border in 2013. Kwesi felt relieved reaching the US border. He thought he would be safe; however, he was detained and thrown into an immigration detention center in San Diego. Kwesi was moved around to several detentions from 2013 to May 2015, when he was finally released from Mesa Verde immigration detention center.

Since his release in May 2015, Kwesi moved to Lafayette California, earned his GED and Medical Assistant certificate, and is working at Whole Foods.

Kwesi, a devoted Christian refused to become the next voodoo priest of his village in Ghana and he was persecuted for it. Fearing for his life he fled to South Africa, through Brazil and arrived at the US border in 2013. Kwesi felt relieved reaching the US border. He thought he would be safe; however, he was detained and thrown into an immigration detention center in San Diego. Kwesi was moved around to several detentions from 2013 to May 2015, when he was finally released from Mesa Verde immigration detention center.

Since his release in May 2015, Kwesi moved to Lafayette California, earned his GED and Medical Assistant certificate, and is working at Whole Foods.

KWESI

Kwesi, era un solicitante de asilo Ghanés que huyó de Ghana escapando de la persecución religiosa. Sin embargo, al llegar a la frontera de Estados Unidos, estuvo detenido indefinidamente durante casi dos años.

Kwesi, un cristiano devoto se negó a convertirse en el próximo sacerdote vudú de su aldea en Ghana y fue perseguido por ello. Temiendo por su vida, huyó a Sudáfrica, atravesó Brasil y llegó a la frontera de Estados Unidos en 2013. Kwesi se sintió aliviado al llegar a la frontera de Estados Unidos. Pensó que estaría a salvo; sin embargo, fue detenido y arrojado a un centro de detención de inmigrantes en San Diego. Kwesi fue trasladado a varias detenciones desde 2013 hasta Mayo de 2015, cuando finalmente fue liberado del centro de detención de inmigrantes de Mesa Verde.

Desde su liberación en Mayo de 2015, Kwesi se mudó a Lafayette California, donde obtuvo su certificado de asistente médico y GED y está trabajando en Whole Foods.

Kwesi, un cristiano devoto se negó a convertirse en el próximo sacerdote vudú de su aldea en Ghana y fue perseguido por ello. Temiendo por su vida, huyó a Sudáfrica, atravesó Brasil y llegó a la frontera de Estados Unidos en 2013. Kwesi se sintió aliviado al llegar a la frontera de Estados Unidos. Pensó que estaría a salvo; sin embargo, fue detenido y arrojado a un centro de detención de inmigrantes en San Diego. Kwesi fue trasladado a varias detenciones desde 2013 hasta Mayo de 2015, cuando finalmente fue liberado del centro de detención de inmigrantes de Mesa Verde.

Desde su liberación en Mayo de 2015, Kwesi se mudó a Lafayette California, donde obtuvo su certificado de asistente médico y GED y está trabajando en Whole Foods.

Rachael

Rachael is a Nigerian asylum seeker who fled her home to escape death because she refused forced marriage. Rachael was raised by her grandparents and when her grandmother died her grandfather arranged her to be married to an 80-year old man. She was taken to be married, but she escaped. She was captured and was detained and tortured with her grandfather. Rachael managed to escape, and her grandfather pled with her to save herself. Rachael found refuge at a pastor’s home. The pastor and his wife helped Rachael flee to Mexico. Upon arriving at the US border, Rachael was detained and transferred to Mesa Verde, where she was held for over one-year. No one knew about Rachael, she was held in Mesa Verde for over 8-months with no single outside contact.

Thankfully Rachael won her asylum case and was released from Mesa Verde. After her release she lived with KWESI volunteers for several months, then moved to Texas to live with a friend. Six months there, Rachael returned to Bakersfield. Rachael moved to Los Angeles to work, and then pursued an RN degree in Texas and is now graduating!

Thankfully Rachael won her asylum case and was released from Mesa Verde. After her release she lived with KWESI volunteers for several months, then moved to Texas to live with a friend. Six months there, Rachael returned to Bakersfield. Rachael moved to Los Angeles to work, and then pursued an RN degree in Texas and is now graduating!

Rachael

Rachael es una solicitante de asilo Nigeriana que huyó de su casa para escapar de la muerte porque rechazó el matrimonio forzado. Rachael fue criada por sus abuelos y cuando su abuela murió, su abuelo dispuso que se casara con un hombre de 80 años. La tomaron para casarse, pero escapó. Fue capturada y detenida y torturada con su abuelo. Rachael logró escapar y su abuelo le suplicó que se salvara. Rachael encontró refugio en la casa de un pastor. El pastor y su esposa ayudaron a Rachael a huir a México. Al llegar a la frontera de Estados Unidos, Rachael fue detenida y trasladada a Mesa Verde, donde estuvo retenida durante más de un año. Nadie sabía sobre Rachael, estuvo retenida en Mesa Verde durante más de 8 meses sin ningún contacto externo.

Afortunadamente, Rachael ganó su caso de asilo y fue liberada de Mesa Verde. Después de su liberación, vivió con los voluntarios de KWESI durante varios meses y luego se mudó a Texas para vivir con un amigo. Seis meses allí, Rachael regresó a Bakersfield. Rachael se mudó a Los Ángeles para trabajar, y luego obtuvo un título de RN en Texas y ¡ahora se está graduando!

Afortunadamente, Rachael ganó su caso de asilo y fue liberada de Mesa Verde. Después de su liberación, vivió con los voluntarios de KWESI durante varios meses y luego se mudó a Texas para vivir con un amigo. Seis meses allí, Rachael regresó a Bakersfield. Rachael se mudó a Los Ángeles para trabajar, y luego obtuvo un título de RN en Texas y ¡ahora se está graduando!

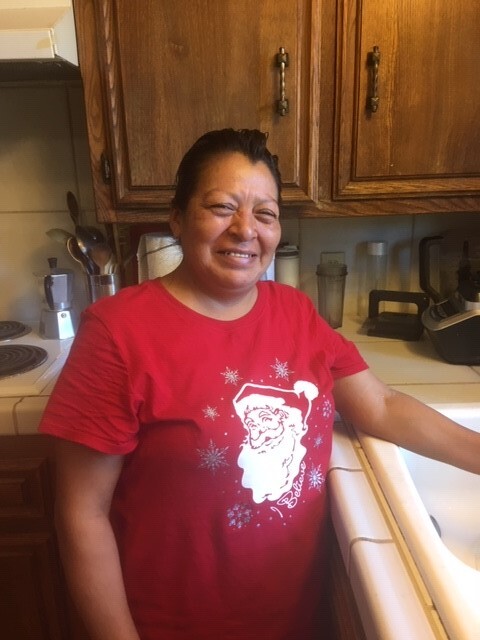

Rebecca

Rebecca was living in Chiapas, Mexico and working for the local government. However, when the 2016 elections started Rebecca, like other government employees were ousted by an emerging corrupt political party. Rebecca was harassed and threatened regularly in public. Rebecca hope that things would eventually calm down, but it did not. Rebecca read regularly that dead bodies of the opposing political party were found throughout the state. Rebecca feared that would be her and her 14-year-old son’s fate, so she fled with her son to the Unites State seeking asylum.

However, when she arrived at the border in April 2019 she was detained and separated from her son. Rebecca spent some weeks at a detention center in Colorado then transferred to Mesa Verde at the end of April 2019. Eventually her son was released to her family in Connecticut.

Rebecca never lost hope of reuniting with her son again, and in mid-June 2019 she was released from Mesa Verde and is now living with her son in Connecticut.

However, when she arrived at the border in April 2019 she was detained and separated from her son. Rebecca spent some weeks at a detention center in Colorado then transferred to Mesa Verde at the end of April 2019. Eventually her son was released to her family in Connecticut.

Rebecca never lost hope of reuniting with her son again, and in mid-June 2019 she was released from Mesa Verde and is now living with her son in Connecticut.

Rebecca

Rebecca vivía en Chiapas, México y trabajaba para el gobierno local. Sin embargo, cuando comenzaron las elecciones de 2016, Rebecca, al igual que otros empleados del gobierno, fueron derrocados por un partido político corrupto emergente. Rebecca fue acosada y amenazada regularmente en público. Rebecca esperaba que las cosas finalmente se calmaran, pero no fue así. Rebecca leía con regularidad que se encontraban cadáveres del partido político opositor en todo el estado. Rebecca temía que ese sería su destino y el de su hijo de 14 años, por lo que huyó con su hijo al Estado de Estados Unidos en busca de asilo.

Sin embargo, cuando llegó a la frontera en abril de 2019 fue detenida y separada de su hijo. Rebecca pasó algunas semanas en un centro de detención en Colorado y luego fue transferida a Mesa Verde a fines de abril de 2019. Finalmente, su hijo fue entregado a su familia en Connecticut.

Rebecca nunca perdió la esperanza de reunirse con su hijo nuevamente, y a mediados de Junio de 2019 fue liberada de Mesa Verde y ahora vive con su hijo en Connecticut.

Sin embargo, cuando llegó a la frontera en abril de 2019 fue detenida y separada de su hijo. Rebecca pasó algunas semanas en un centro de detención en Colorado y luego fue transferida a Mesa Verde a fines de abril de 2019. Finalmente, su hijo fue entregado a su familia en Connecticut.

Rebecca nunca perdió la esperanza de reunirse con su hijo nuevamente, y a mediados de Junio de 2019 fue liberada de Mesa Verde y ahora vive con su hijo en Connecticut.

Sharon

Call Her by Her Name

A piece written by Julie Jordan Scott

Julie is one of KWESI's dedicated volunteers and has shared

with us an experience she and Sharon, an immigrant from Cameroon,

endured traveling through the LAX airport.

The first time I was aware of namelessness was last September, when I was visiting a woman who was being detained at Mesa Verde. One of the guards who I had liked until that point said, “Are you here to visit 32Up?”

I responded, “I am here to visit Queenta.”

“32Up?” she asked again.

“I am here to visit Queenta.” I said again, emphasizing “here” and “Queenta.”

The guard turned her face and called the dorm to get Queenta ready for her visit. “She isn’t a bed number, she is a person,” I muttered under my breath.

Ironic that her name includes the title “Queen.”

At Los Angeles International Airport last Friday night, I was with a woman named Sharon. She, like most of the women I have met from Cameroon, has a story that goes far beyond what my privileged white background can begin to imagine. She is twenty-four-years-old yet seems much younger. She talked with a soft voice and as we spent our final moments together, two big tears fell down her face as she whispered, “Thank you for coming here to see me on my way, Mom-Julie”

I knew she didn’t feel well. I wished she was leaving under better circumstances.

I was thrilled when the United Airlines employee waved Sharon through to the gold line so she didn’t have to wait. Once she got to TSA it was a different story. She was flagged by the agent and had to wait to have her bag inspected, her papers inspected and her body frisked.

I was separated from Sharon because she had a ticket and I didn’t.

She was in a zone I couldn’t get into so it felt as if I was no longer eligible to advocate for her. A ticketed man came through the line and I said to him, “Excuse me, will you tap her shoulder so she can see I am trying to talk to her.”

He was happy to help and when she turned and came closer I told her, “I will not leave until you are through.”

I could tell she was feeling worse and worse physically as she waited by the XRay machine. I saw her stumble a bit, almost fainting. I saw the TSA staff get her into a wheelchair. I saw her head hanging down. I couldn’t tell if it was because she was discouraged or if she had lost the strength to hold it up.

I noticed a staff person with CLEAR, an agency that accepts a fee that allows people to get through TSA quickly and easily, was watching us. Her work station was immediately adjacent to the TSA staff in a place I couldn’t access. “Excuse me,” I said to her, “Will you please get one of the TSA’s attention? I am with that girl, the one in the wheelchair – I think she might be having a problem.”

“Do you want to come up here?” she said, pointing to the rope between me and the TSA where only ticketed passengers usually stand.

“Yes,” I said, “But can I?”

“I’m saying you can,” she said, calling out “Hey, TSA guy, this lady needs your help.”

The TSA man looked at me, curiosity in his eyes. “That girl, in the wheelchair,” I said, “Can you get her water or juice or something? She isn’t feeling well.”

The TSA agent was a young man, he said “I think she passed out, I don’t know what to do,” and he called out to his colleagues who were closer to Sharon. “This lady is with that girl, is she ok?”

He turned back to me, “I don’t think she is conscious.”

My fear reared up and I shouted, “Call her by name. Her name is Sharon, call her by name!”

I yelled “Sharon!” and a chorus of “Sharons” rang out. I said Sharon and at least four TSA agents followed suit. Immediately Sharon jumped up and turned to me. “Mom!” she said and waved, weak and smiling.

“Drink water, please, when you get back there.”

“Get her a wheelchair attendant!” yelled the Clear employee who had become an advocate as well.

Sharon got up and walked through the XRay machine. They frisked her on the other side and put her luggage back together and she was, indeed, awarded a helper in the guise of a wheelchair attendant.

She looked over her shoulder at me and smiled.

“Call her by name,” I whispered to no one and everyone. “Her name is Sharon.”

Sharon called me yesterday from her new home in San Antonio. She was meeting other members of the Cameroonian community and settling into her new life where I trust from now on she will be known as Sharon, Friend, Sister, Auntie, Beloved and perhaps someday, Mommy.

A piece written by Julie Jordan Scott

Julie is one of KWESI's dedicated volunteers and has shared

with us an experience she and Sharon, an immigrant from Cameroon,

endured traveling through the LAX airport.

The first time I was aware of namelessness was last September, when I was visiting a woman who was being detained at Mesa Verde. One of the guards who I had liked until that point said, “Are you here to visit 32Up?”

I responded, “I am here to visit Queenta.”

“32Up?” she asked again.

“I am here to visit Queenta.” I said again, emphasizing “here” and “Queenta.”

The guard turned her face and called the dorm to get Queenta ready for her visit. “She isn’t a bed number, she is a person,” I muttered under my breath.

Ironic that her name includes the title “Queen.”

At Los Angeles International Airport last Friday night, I was with a woman named Sharon. She, like most of the women I have met from Cameroon, has a story that goes far beyond what my privileged white background can begin to imagine. She is twenty-four-years-old yet seems much younger. She talked with a soft voice and as we spent our final moments together, two big tears fell down her face as she whispered, “Thank you for coming here to see me on my way, Mom-Julie”

I knew she didn’t feel well. I wished she was leaving under better circumstances.

I was thrilled when the United Airlines employee waved Sharon through to the gold line so she didn’t have to wait. Once she got to TSA it was a different story. She was flagged by the agent and had to wait to have her bag inspected, her papers inspected and her body frisked.

I was separated from Sharon because she had a ticket and I didn’t.

She was in a zone I couldn’t get into so it felt as if I was no longer eligible to advocate for her. A ticketed man came through the line and I said to him, “Excuse me, will you tap her shoulder so she can see I am trying to talk to her.”

He was happy to help and when she turned and came closer I told her, “I will not leave until you are through.”

I could tell she was feeling worse and worse physically as she waited by the XRay machine. I saw her stumble a bit, almost fainting. I saw the TSA staff get her into a wheelchair. I saw her head hanging down. I couldn’t tell if it was because she was discouraged or if she had lost the strength to hold it up.

I noticed a staff person with CLEAR, an agency that accepts a fee that allows people to get through TSA quickly and easily, was watching us. Her work station was immediately adjacent to the TSA staff in a place I couldn’t access. “Excuse me,” I said to her, “Will you please get one of the TSA’s attention? I am with that girl, the one in the wheelchair – I think she might be having a problem.”

“Do you want to come up here?” she said, pointing to the rope between me and the TSA where only ticketed passengers usually stand.

“Yes,” I said, “But can I?”

“I’m saying you can,” she said, calling out “Hey, TSA guy, this lady needs your help.”

The TSA man looked at me, curiosity in his eyes. “That girl, in the wheelchair,” I said, “Can you get her water or juice or something? She isn’t feeling well.”

The TSA agent was a young man, he said “I think she passed out, I don’t know what to do,” and he called out to his colleagues who were closer to Sharon. “This lady is with that girl, is she ok?”

He turned back to me, “I don’t think she is conscious.”

My fear reared up and I shouted, “Call her by name. Her name is Sharon, call her by name!”

I yelled “Sharon!” and a chorus of “Sharons” rang out. I said Sharon and at least four TSA agents followed suit. Immediately Sharon jumped up and turned to me. “Mom!” she said and waved, weak and smiling.

“Drink water, please, when you get back there.”

“Get her a wheelchair attendant!” yelled the Clear employee who had become an advocate as well.

Sharon got up and walked through the XRay machine. They frisked her on the other side and put her luggage back together and she was, indeed, awarded a helper in the guise of a wheelchair attendant.

She looked over her shoulder at me and smiled.

“Call her by name,” I whispered to no one and everyone. “Her name is Sharon.”

Sharon called me yesterday from her new home in San Antonio. She was meeting other members of the Cameroonian community and settling into her new life where I trust from now on she will be known as Sharon, Friend, Sister, Auntie, Beloved and perhaps someday, Mommy.